The Angry Drunk Bureaucrat's perenial nemesis Richard Florida is out with a new tome with the panic induced title of FLIGHT OF THE CREATIVE CLASS: The New Global Competition for Talent. Michael Madison is blogging about it over at his place, so I figure it's now fair game for me. I figured that ganging up might be unfair as my antipathy for Dr. F. is fairly well known. Lord knows that the literally 3 people that read this blog care so much about the creative dynamics in economic development and my views on the subject. I decided to get over myself, and lay into the guy again.

My views in sum: Florida is sound and fury, signifying nothing. Or, alternatively, Florida is like Oakland California: when you get there, there's no there there. I consider him to be an academic snake oil salesman... but a damned fine one, I must say.

Business week has a review of his new book. I thought I'd share, as I have the time and space and I don't think Business Week has a free site: Business Week May 16, 2005

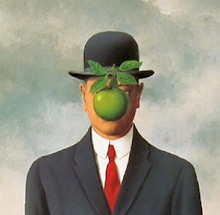

I suppose I could have summarized this review in one pithy saying:

Copyright 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. http://www.mcgrawhill.com

All Rights Reserved

Business Week

May 16, 2005

SECTION: Books; Pg. 16 Vol. 3933

Talent: Will America Lose Out?

By Aaron Bernstein

FLIGHT OF THE CREATIVE CLASS

The New Global Competition for Talent

Richard Florida

HarperBusiness; 326pp; $25.95

Richard Florida has been something of a hero among civic activists and urban planners since the 2002 publication of his The Rise of the Creative Class. In that book, the George Mason University public policy professor argued that the growth of advanced economies like America's is driven largely by knowledge workers such as scientists, engineers, managers, professionals, and artists. For cities and regions to thrive, he said, they must foster a welcoming environment for such people.

Now, Florida is back with The Flight of the Creative Class: The New Global Competition for Talent, a sequel that extends the argument internationally. Florida's basic point is that the entire global economy increasingly revolves around innovations that flow from the creative classes. In this rapidly emerging competitive environment, he says, the U.S. is in danger of losing its crucial advantage as the world's greatest talent magnet. Social and economic inequality, growing political intolerance, and a faltering educational system are making the U.S. less attractive to a global class of workers whose skills are in rising demand everywhere, from Europe to India and China. This is America's most serious long-term threat, warns Florida, ``because wherever talent goes, innovation, creativity, and economic growth are sure to follow.''

It's a compelling and seductive thesis, backed up by voluminous statistics and analysis. Too bad it's such an incomplete description of how economies actually work. While there's a good bit of value to Florida's insights, he doesn't account for U.S. and European job flight caused by low wages abroad. His analysis also turns on the unproven -- and overblown -- assertion that talented workers are free to change jobs, cities, and countries whenever they see more attractive prospects.

Unfortunately, even the core data Florida uses to prove his thesis explain less than he claims. To show that America's predominance is threatened, he constructs an index of the world's creative classes based on occupations that involve creative thinking. There are up to 150 million such workers in the 39 countries for which he can find reliable data. The U.S. still has the greatest number, with more than 30 million, and the greatest share of the total, at about 20%. But if you take such workers as a share of each country's own workforce, the U.S. ranks only 11th out of 39. ``Far from being the world leader, we are not even in the top five,'' warns Florida.

Problem is, he's defining the creative class by people's occupation alone, rather than years of schooling, the more conventional gauge of workforce ability. And by the latter measure, the U.S. remains No. 1. Florida concedes the point in a brief sentence, but he argues that his approach is better because a focus on education misses the contributions of accomplished college dropouts such as Microsoft Chairman William H. Gates III. True enough, but his occupation metric skips people, too. Florida has a point when he warns of America's slipping workforce competitiveness, but it would be better made by focusing on its underinvestment in education.

The bigger problem is Florida's assumption that ``talented people are a global factor of production, able to choose among economically vibrant and attractive regions of the world.'' There is of course some truth in this, as demonstrated by the large number of Asian graduate students in U.S. science and engineering programs.

But this is way too rosy a description of the experience of skilled workers, who quickly accrue what economists call ``firm-specific human capital.'' In other words, most professionals learn skills specific to their companies and can't easily jump ship when they spy a better employer -- or country. There are other deterrents too, such as the stress of uprooting one's family or the difficulty of securing a work visa. It would be great for workers if companies and countries had to compete head-on in a global talent pool, but that happens only on a limited basis -- not enough to drive entire economies.

Finally, there's the little matter of wages. Florida isn't an economist, and it shows. In his world, talent moves to the best environment. But what about U.S. jobs that flee to low-wage countries? He dismisses competition from India and China by saying that those countries rank low on his global creative class index. In other words, only 1.4% of China's 745 million-plus workers have a college degree, vs. nearly 30% in the U.S. True enough, but since China's 10 million college grads are available at a dime on the dollar compared with U.S. workers, why exactly would multinationals kill themselves to please America's creative classes, as Florida suggests?

Still, Florida's main point is a good one: For the U.S. to remain globally competitive, it must do a much better job of investing in its skilled workforce.

For Florida, economics is bunk.Of course, as I've said before, economics is most definitely not bunk and that the pull of "creativity" will be trumped by economic expediency.

No comments:

Post a Comment